How to organize your inventory management team for maximum impact?

Jun 11, 2014 • 13 min

We are often asked what resources, skills and degree of centralisation are needed to make the replenishment process as efficient as possible and get the maximum benefits from a better system. There isn’t a single one-size-fits-all template because every company is unique in its corporate culture, business model and practices. Even so it’s still useful to take a look at how others have gone about it.

At RELEX we’ve collated information from more than a dozen of our large customers about how they have chosen to organize their replenishment. We’ve also come up with recommendations based on the approaches we’ve seen that work well in tackling the challenges our customers have faced.

Global Vs. Local in Multinational Organisations

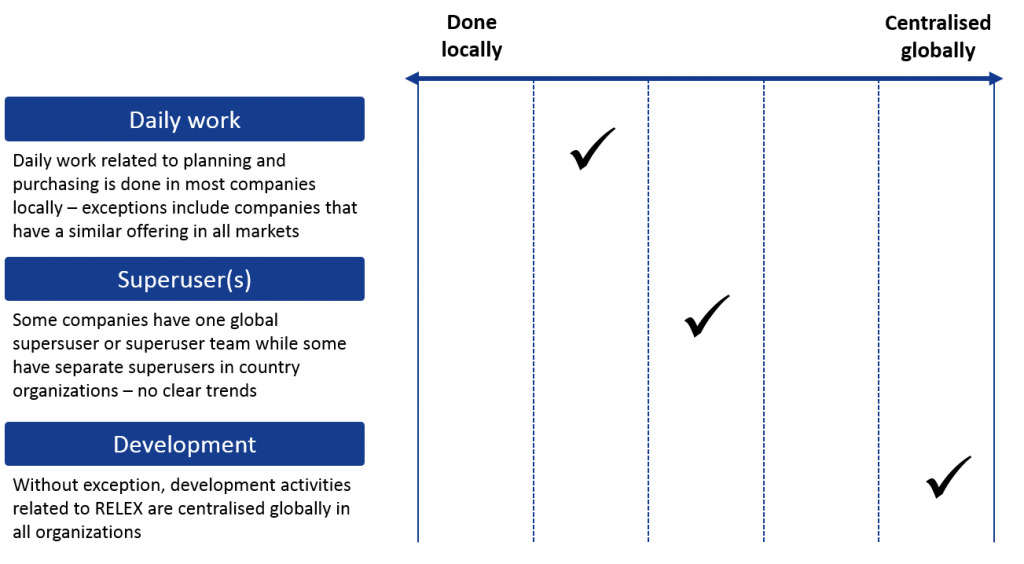

Among the multinationals we work with the more their global operations are harmonised the greater the tendency to bring inventory and replenishment under central control. Where different territories retain a strongly local flavour it’s more likely that a significant part of their replenishment will be managed locally. The development of system support is, without exception, handled by a single, central team, while operational purchasing and replenishment is, on the whole, handled locally (Figure 1).

Operational Purchasing and Replenishment

Multinational companies often drive growth by acquiring local operators. In some cases work practices, assortment and customers all retain strong local characteristics. In wholesale large local customers often have a significant impact on both assortment and demand, which tends to suggest that there needs to be close cooperation with product managers and customer service managers in the daily management of the supply chain. In such cases it’s common sense to manage operational replenishment locally.

Companies, especially retailers, who take a single unified concept and assortment into all their markets have, on the other hand, decided to centralise replenishment through a global team. In many cases, responsibilities are split between members of the team, so that a particular person or group will be in charge of a certain market or markets. By centralising replenishment economies of scale are achieved both through increased volumes and by applying best practice across all their markets. It also has the virtue of allowing best practice to be shared easily. Members of the team quickly learn from one another’s successes and mistakes and the team progresses and develops rapidly together.

System Responsibility and Development

All our customers have decided to centralise development issues that involve system support. There are clear advantages with this. Firstly the development benefits flow through to every territory. Secondly, the risk of the system support developing in different directions in different countries is reduced.

Some of our customers have also appointed global super-users for the system, while others have chosen local super-users in each market. Where a super-user sits within an organisation depends heavily on their work priorities:

- If the focus is on supporting the daily work of replenishment planners, it is natural that the role of the super-user is local and close at hand.

- Where the focus is on improving processes and system usage, the super-user’s natural role is a global one with a close connection to development.

If all super-users are local there is a risk that it becomes unclear who ‘owns’ the system. When development decisions are made globally it can be hard for the local organisations to get their support needs met and that, in turn, risks local teams losing interest in the system’s ongoing development.

Even when there are reasons for working on operational supply chain management at a local level, we recommend the following organisational model for multinationals:

- A single global super-user in charge of the development of system support and processes.

- Local super-users supporting local replenishment planners in their daily work and being responsible for introducing agreed-upon process improvements and system usage.

By creating forums where supply chain managers from the various countries in which the group operates meet regularly and exchange ideas, tips and experiences, it becomes easier to ensure that local managers have the same level of knowledge of the system and that unified development across the company can be supported.

Demand Planning and Operational Replenishment

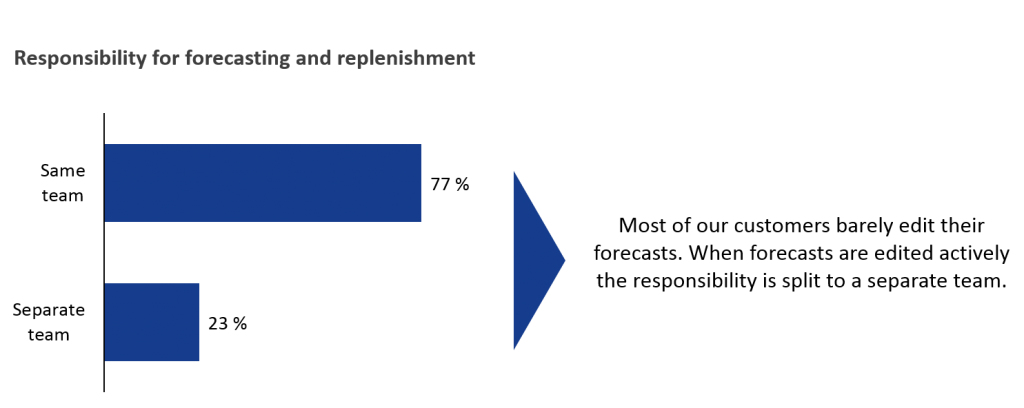

The vast majority of our customers, and almost 80% of the companies included in this study, rely to a high degree on the forecasts that the system calculates. This can also be seen in how our customers have decided to divide the responsibilities of demand planning; only a few companies have separated the responsibility for replenishment and forecasting (Figure 2).

Forecasts Calculated by Systems Are Widely Used

Where lead times are short and frequency of deliveries is high the significance of forecasts for efficient replenishment is relatively low. In this situation store replenishment forecasting is but one of a number of parameters that affect shelf availability and inventory levels. We estimate that amongst all the relevant factors it accounts for about 15% of overall performance. In these cases there is generally no need to edit the forecasts that the system calculates.

Those of our customers who do not regularly edit their forecasts let the replenishment team update the forecasts when necessary. Generally when planning major campaigns, or updating forecasts for bestselling articles in high season, the replenishment team is assisted by category or product managers. How the information exchange is executed varies a lot: from ad hoc to clear processes.

The active involvement of category or product managers in planning, or at least in monitoring demand for bigger campaigns and bestselling seasonal articles, is something that our customers could make even more use of and do so more systematically. Firstly, this results in more proactive planning and less fire-fighting. Secondly, active monitoring serves to increase knowledge and improves the decision making environment for future decisions regarding market activities and assortment.

When Forecasts Are Edited Actively, the Responsibility Lies Outside the Replenishment Team

When lead times are long, the articles have a high value or extremely short life cycles or when customers’ purchasing patterns have a significant effect on demand, actively editing forecasts has a bigger impact. In these cases it is simply more important that the forecasts reflect the best available information about the products and the market.

For these reasons, some of our customers have decided to split the responsibilities for operational purchasing and demand planning. These companies have either created a dedicated team for demand planning or organisationally given product or customer managers ownership of the forecasts. The return on this investment of time and resources can be seen in terms of higher forecast accuracy.

Even if it requires a lot of education and change management, there can be significant advantages in dividing the responsibility for purchasing and demand planning, at least within larger wholesalers whose demand is highly customer driven or whose assortment changes frequently. If demand is driven by customers’ assortment decisions or production plans, forecasts at the customer level or customer-group level can, by actively involving customer managers, capture the available information on customers’ planned changes in purchasing more effectively.

Warehouse Purchasing and Store Replenishment

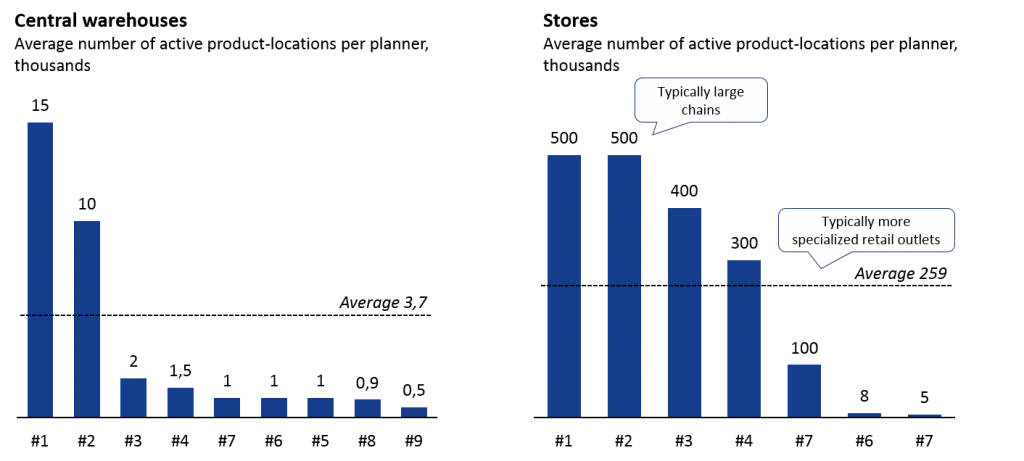

When looking more closely at resource needs in replenishment, it becomes clear that there are big differences in the number of active product-locations that a planner can handle in warehouse purchasing compared to store replenishment (Figure 3).

In larger chains at store level the average number of active product-locations (that is combinations of articles and stores) is 280 000. Within smaller chains handling high-value special products or products with very short life cycles a planner can handle several thousand active product-locations. The average active product-locations per planner in wholesale is 3 700 but it can exceed 10 000, primarily at warehouses that deliver to larger chains.

There are several reasons for warehouse purchasing being more resource intensive than store replenishment:

- Lead times for warehouse purchasing are often long, which implies that every purchase decision has a bigger financial significance.

- There is more uncertainty and variation in supply reliability, and also a greater need for time consuming delivery monitoring.

- The replenishment team often has to take capacity restrictions into account in warehouse purchasing.

Additionally, economies of scale in store replenishment, as opposed to warehouse purchasing, are achievable because it’s possible to control campaigns and assortment shifts across the whole chain or large groups of stores.

Despite this, our experience is that efficiency in warehouse purchasing could be a lot higher than it is now. When companies have decided to automate and centralise store replenishment, processes and the organisation have, in many cases, been built while the system is being introduced. Obviously introducing any new system involves challenges however its flexibility means that it doesn’t ‘force’ clients to operate in a particular way (albeit it does require certain things – for instance good input data is essential and it’s a prompt to address any shortcomings there may be in data quality) but rather provides an excellent ‘new beginning’ to optimise processes. These processes are developed around the business’s current needs (whereas a lot of legacy processes reflect where a business was at the time they were developed rather than where it is now) and a team with the right competence has been established. At the outset of system implementation projects we almost always find old working habits and an existing team in the background within the warehouse purchasing operations. In some cases, the transfer from routine-based ordering to data-based forecasting and purchase proposals together with exception based routines has not succeeded to the fullest either because change management is not handled as well as it could be or because it isn’t possible to develop the necessary skills and competencies within the team.

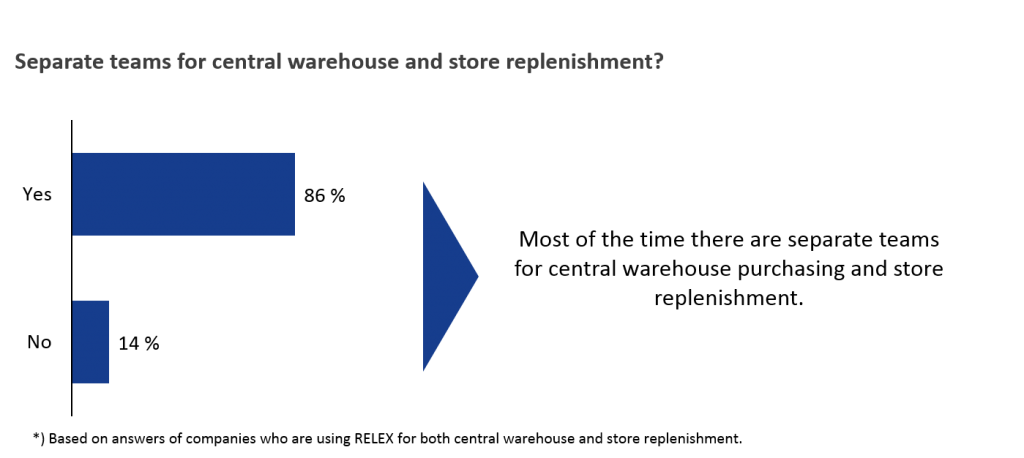

Among the customers who use RELEX system support for purchases for one or more warehouses and for store replenishment, the vast majority have decided to divide the responsibility for each flow (Figure 4).

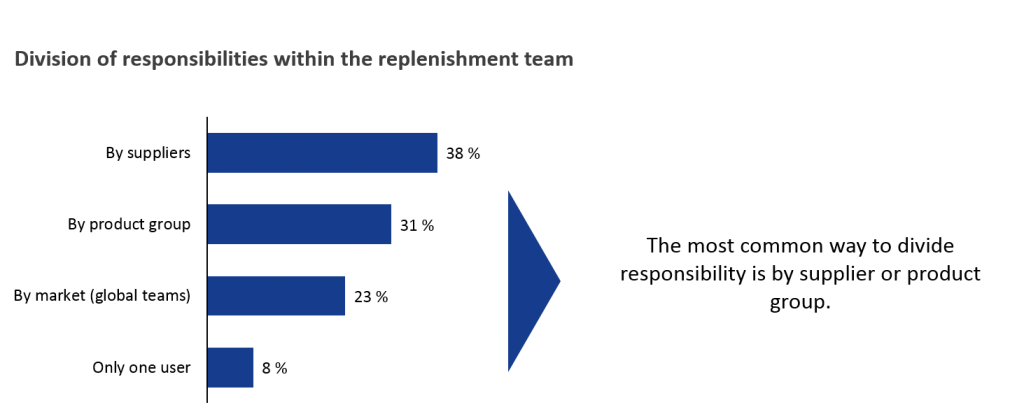

When looking closer at the areas of responsibilities within the teams, what can be said is that the two most common models are that team members are in charge of different suppliers or product groups (Figure 5). Among multinationals it is common that responsibilities are divided into markets.

Development and Leadership

Good system support for supply chain management allows the entire material flow to be adjusted very efficiently through changes to the rules that control the system’s parameters, rather than by making changes manually at individual-product level. Thus the replenishment process changes from one where it’s all hands-on management and constant fire-fighting to one whose focus is continuous monitoring and development. To achieve the best results from this change clear, strong leadership is needed to ensure that development remains aligned with the business’s strategy and priorities.

Role of the Super-user

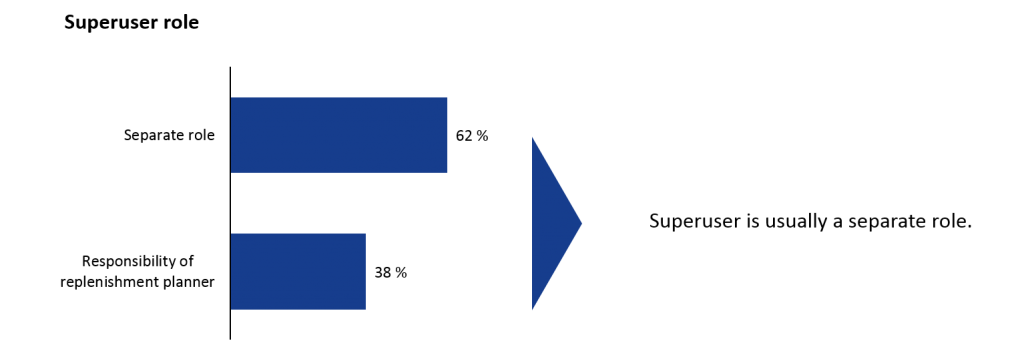

The majority of our customers have a separate super-user for the system (Figure 6). In some cases this super-user’s focus is on developing the system’s functionality and its parameters, but in many cases this role is combined with the leadership of the replenishment team or with responsibility for development. It is also common that one or more of the operational replenishment planners takes on the super-user role.

Because RELEX’s support system is configurable and can be monitored against the KPIs and criteria set by the super-users, the super-user is in a pivotal role when it comes to ensuring that the best results are achieved.

Thus, among other things, the role of the super-user is:

- To analyse recurrent exceptions and manual corrections in the purchase proposals in order to understand the underlying causes and to fix these by updating the rules and parameters.

- To analyse the key ratios of replenishment and the underlying reasons in order to find opportunities to improve results.

- To support the replenishment planners in their daily work by introducing improvements in order to maximise the efficiency of their work routines.

We recommend that the system’s super-user is not given operational responsibility for placing orders, or at least that such work is kept to an absolute minimum. A good super-user will affect the efficiency of the whole replenishment team through their understanding and control of both the system and the overall process, and through the adjustments and improvements they make. It’s no exaggeration to say that every improvement pays for itself many times over. If lots of the super-user’s time is tied up in placing orders, there’s less time for initiatives that raise the level of the whole team. Since the super-user’s most important tasks are to analyse the whole operation and to identify well targeted measures to improve it, he or she also has to be able to step back and look objectively at the big picture, rather than be left to make fast, instinct-driven decisions. This is hard to achieve if the person is simultaneously working in the frontline.

With some of our customers we can see that they’re genuinely interested in developing both processes and system usage, but because day-to-day operational work always has to be done nowdevelopment initiatives all too often get sidelined or postponed indefinitely. This brings to mind the old story of the man running beside his bike; when asked why he’s not riding he replies that he bought the bike because he is in a real hurry to get somewhere but because he’s in such a hurry he hasn’t had time to actually learn how to ride it.

Leadership

Another very important question about the organisation, one that is extremely hard to quantify, is what kind of backup the replenishment team receives. The replenishment team is often under pressure from many directions: the store operation often reacts strongly when something goes wrong even if it is just about a single article in a hundred; the supply chain manager’s goal is to optimise the handling and transport costs; the sales manager would like to see fully stocked shelves; management aims to reduce the amount of capital tied up in inventory.

We have heard horror stories about sales managers running to the replenishment team and frantically showing them pictures of shelves that are not adequately filled. You hear about e-mails, regarding some article that has run out, that have been circulated around the whole organisation right up to group management. This is often despite the fact that an objective evaluation of the situation has shown that all key ratios have developed in the right direction, shelf availability has improved by several percentage points and the fill ratio of shelves corresponds to established goals.

In order to avoid a situation where everyone is trying to shout the loudest, good leadership that takes corporate strategy and presents it as concrete goals and priorities, is needed. Then the replenishment team can use these to guide their everyday work. Measurable goals are necessary for the continuous evaluation of the operations.

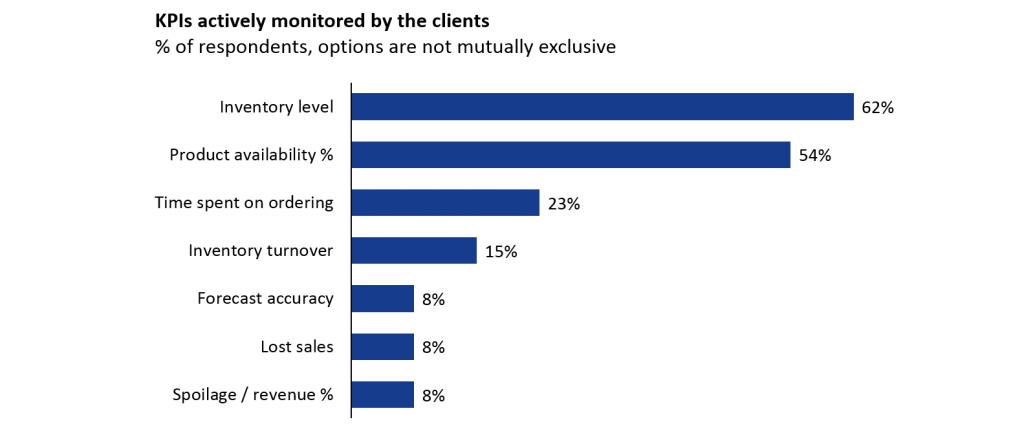

Inventory level and availability are the key metrics that most of our customers follow (Figure 7). Additionally time spent placing orders is typically closely monitored, particularly during and right after the implementation phase, because making work practices more effective is often a key goal for clients implementing a new support system.

Most companies are very good at following up key metrics during the implementation phase of a new support system, but occasionally we find a lack of clear goals, rooted in corporate strategy, to guide ongoing development. If the performance of the replenishment process is not monitored, there is a serious risk of development being interrupted and of reversion to pre-existing routines.

The need for clear goals across the whole organisation is even plainer when the direct benefits of a better support system are brought home. When a certain level is reached, the assortment decisions within the category function and the campaign decisions within the sales or market functions begin to set limits for further improvements in replenishment (Figure 8).

Conclusions

By introducing a better support system more efficient work routines and increased accuracy are achieved. By simultaneously following up the processes and the organisation so that the available data, resources and skills are focused in the best way, the effect will be even greater. RELEX’s customers have, for instance, managed to reach record levels of availability and service, while inventory levels and staff time used placing orders have clearly decreased. Proper management and the right skills ensure that the results are continuously improved.

Organizing your replenishment operations is one important part of a successful supply chain transformation process. If you want to learn what are the other steps, read our ‘Supply Chain Transformation: The Complete Guide’.