Prescription for pharmaceutical distribution: Keeping the balance between availability and speed of service with shifting models and regulations

Sep 19, 2022 • 14 min

Pharmaceutical distributors perform a complex balancing act between suppliers and retailers, facing challenges and circumstances that distributors and wholesalers in other retail verticals do not. In many ways, they are similar, but some critical distinctions mean higher pressure and the need for rapid response to changes in the market that can affect not only consumer satisfaction but their economic and physical well-being.

Striking the balance between availability requirements and inventory cost

When it comes to supply chain and inventory management, what are the key concerns that pharmaceutical distributors face?

- Availability targets are high and subject to regulation. Ensuring the high availability levels required by government regulation means that distributors must always maintain high stock levels, which can carry significant costs.

- Most distributors serve industries beyond retail. Varied customers such as hospitals, healthcare, and emergency services have different needs than retail pharmacies. Order volume, frequency, and demand shifts can fluctuate dramatically, and distributors must execute all from the same facilities.

- Changing regulations are causing shifts in operational models and assortments. In some areas, distributors are only beginning to expand into the retail side of their business by acquiring outlets and broadening their assortment offerings.

- Suppliers impact inventory decisions as much or more than retailers. In some cases, agreements with pharmaceutical suppliers and manufacturers can influence distributors’ inventory planning more than demand signals from the retailers.

- Substitutions come with their own complexity. Most regions have a vast substitution market to cover shortages, but with constant pricing shifts driving healthcare and insurance providers’ preferred drug changes, managing substitutions comes with its own complexities.

With so many dynamics, retaining accuracy in supply chain planning and execution can be difficult. It is critical to find a solution that can seamlessly handle additions of new product categories, sales channels, or depots. The solution needs to be able to quickly adapt to cover new purchasing restrictions and changes in stock holding strategies such as adding hubs, regional DCs, or changes in service models. Finally, it needs the capability to simulate the operational effects of any changes across all stock holding locations.

Section 1: Regulated availability targets increase pressure on distributors

Most pharmaceutical distributors have the same issue at the top of their list of core challenges: how to maintain high inventory levels while keeping costs under control. In most countries, government legislation mandates availability targets, and the pressure to secure them is high. Holding inventory to guarantee availability comes with considerable costs; even minor changes in inventory decisions can significantly impact those costs.

One consideration for deciding how much inventory to hold is product type. Demand for prescription drugs tends to stay relatively flat for common and rare illnesses. For these regulated drugs, even though distributors need to always have access to mandated targets, for some products, they may have more flexibility in purchasing and holding.

For example, Drug A is typically ordered from the supplier once a week with a three-day lead time, and that demand cycle is typical. However, in an emergency, the distributor can place an additional order with a shorter lead time from the same supplier. This extra order will have a higher cost to fulfill, but that may not be greater than the cost to hold the excess product in the first place.

Distributors need the ability to reconcile the costs of each product type and its fulfillment options when making inventory decisions.

Further, most regions have vast substitution markets to cover any shortages. So, should an issue with a given supplier or an external factor such as an outbreak occur, distributors need to be able to assess options for needed products across all available channels to ensure that they are meeting availability requirements at speed and with the most economical choice possible.

Availability concerns do not only apply to prescription drugs

While some pharmaceutical distributors elect to keep their offerings limited to medicines, many are expanding their assortments to include over-the-counter (OTC) drugs, health and beauty products, and more.

OTC drugs, like seasonal allergy and cold medications, are not as highly regulated but have similar cost issues regarding availability targets. Demand shifts for seasonal and slow-moving drugs can be unpredictable due to weather changes, environmental drivers such as allergens or outbreaks, or market drivers such as price and promotions.

Storage space and order frequency are the most typical drivers of replenishment challenges for fast-moving medications. For slow-moving or seasonal products, distributors will not have a lot of sales data available to them. When data is particularly sparse, an advanced system can take the information they have and generate forecasts on multiple aggregate levels to help estimate demand-influencing factors and increase accuracy.

To manage availability for various product types, distributors need a system that enables them to create and revise rules quickly and efficiently to drive inventory decisions. That system would automatically assess retail data, such as the frequency of sales against the expense of carrying the product, to determine whether the distributor should hold an item and in what quantities.

Swiss pharmaceutical wholesaler Galexis manages more than 120,000 order lines and 4,000 deliveries a day. By automating replenishment processes, they increased inventory turns by 12% and raised automation from 44%-88% while maintaining 98% availability. Further, the system issues warnings when fluctuations in demand or possible stockouts are detected and automatically proposes an urgent delivery.

Further, waste is a risk that affects availability and cost. Distributors must also be able to build rules for expiration dates and any special storage needs such as temperature control. They must be able to reconcile the cost of high inventory levels against the expense of managing the inventory itself, particularly in the case of one-off prescriptions.

Section 2: Multiple customer types have unique requirements for order volume, frequency, and speed

Maintaining availability in the distribution centers is only half the battle. If distributors cannot deliver medications where and when needed, serious repercussions are almost inevitable. Speed of service is critical for prescription drugs, and distributors must manage the logistics of their varied customers.

For example, deliveries to retail pharmacies are small and intraday, necessitating high handling capacity at the DC. Distributors need optimized warehouse processes to effectively manage a vast amount of order lines in small volumes and multiple locations, all in a short time.

Hospitals and other healthcare agencies typically place higher volume orders with less frequency. Further, government-mandated safety stock levels mean that, in an emergency, there is a potential need to respond quickly to sudden demand spikes. To manage the high-capacity requirements of the small, intra-day orders and the larger, less frequent orders – and be sufficiently prepared for an emergency spike – distributors need a system that can process diverse order types for all situations from a central location. Examples include:

- Virtual ringfencing effectively serves multiple customers and channels from the same inventory pool, ensuring that one high-volume customer does not take stock away from another potentially important lower-volume customer.

- In shortage situations, distributors can prioritize customers when allocating available stock, giving each their fair share according to strategic importance.

- Both customer orders, as well as orders to suppliers, can be assigned a type to prioritize replenishment or to drive custom logic, such as allowing orders with a shorter lead time.

Section 3: As regional regulations change, distributors are rethinking their operational models and offerings

The landscape of operational models is shifting in many areas of the world

While the specific operations and requirements vary from region to region, pharmaceutical distributors have two core functional distinctions: those that own retail outlets and those that do not. Today, however, the lines are blurring, and many distributors are looking for ways to shift in different directions.

Traditional wholesale model

Distributors who do not own pharmacies but act only as a wholesaler between the manufacturer and third-party retail and non-retail customers have been the most typical model in many regions. In some regions, this is because of government regulations restricting the ownership of retail outlets by the distributors.

The advantage of the traditional wholesale model is that the distributor focuses solely on capabilities in the distribution centers and does not split attention between DCs and store operations. Further, if they are the only distributor of a specific product, they can focus on all customers and channels equally, not as owned or third-party outlets.

Data quantity and quality, however, are causes of complexity for traditional wholesalers. They do not have access to the same level of demand data from their retail – and non-retail – customers as distributors that own their outlets. This lack of data means these distributors must develop aggregate strategies such as ramp-ups and downs for slow movers and seasonal items. Further, since distributors cannot allocate seasonal products for third-party stores in advance, they have no option but to keep all the inventory in their DCs, which increases holding costs.

The trade-off for lower data levels is the need to carry higher stock levels and the potential for increased purchase frequency to account for the loss of accuracy.

Owned pharmacy model

Some regions have always allowed pharmaceutical distributors to own their retail outlets. In other areas, especially in Europe, recent restriction changes mean distributors are now permitted to acquire independent pharmacies. This trend gives distributors clear advantages but also comes with additional complexities they may not have previously faced.

The primary benefit for distributors who own the retail outlets is access to data. The level of visibility into sales and forecast data from owning the stores they serve gives distributors the advantage of proactive planning for seasonal and promotional products and demand shifts due to substitutions. However, complexity arises for those distributors who are newly entering the retail side of the business. They must now contend with issues such as assortment and space planning, managing inventory across multiple sales channels, and managing consumer expectations and satisfaction.

Additionally, for more prominent distributors, their owned pharmacies may only be one part of the demand they fulfill. As discussed earlier, they may have to serve non-retail entities such as hospitals, government facilities, and other healthcare agencies.

Mixed model approach and Vendor Managed Inventory (VMI)

Despite the complexities, in many areas of the world, the lines are blurring, and distributors on both sides of the spectrum are shifting to a mixed-model system, acquiring independent outlets and serving both owned and third-party retailers and non-retail channels. Many are adding VMI offerings to boost efficiency and accuracy for their third-party customers.

A mixed-model system gives distributors a more robust customer base and the opportunity to incorporate a more extensive assortment, such as health and beauty and other general assortment items. While some distributors may elect to offer a purely medical assortment, a trend is emerging, especially in Europe, toward this assortment expansion. However, though the benefits are numerous, the wider the assortment, the more complex the DCs become, particularly when managing slow movers and promotions.

Further, increasing the client list means sales growth potential, but it also increases the range of an already diverse group of customers. As the customer list grows, each must be prioritized and treated differently based on their unique needs. Additional customers also bring the potential for new channels, including online and types of new non-retail channels. New and expanding sales channels are a significant source of complexity regarding segmenting inventory, deciding stock levels, and executing orders.

Adding VMI as a service enables distributors to help independent pharmacies manage daily replenishment to improve customer service, optimize product assortment, and maintain margins. By extending their service to cover customers’ replenishment directly, they can mitigate some of the issues caused by a lack of data and create an integrated supply chain model that functions the same as if they were delivering to their own pharmacies.

Italian pharmaceutical wholesaler Unifarm supplies around 41,000 SKUs to 1,900 independent pharmacies across Northern Italy and Sardinia. Using automated and adaptive forecasting and replenishment capabilities in their VMI offering has resulted in a 30% inventory reduction, a 20% reduction in lost sales, and an average of 2 hours per day saved on manual replenishment processes for the pharmacies that use the service.

The highly automated warehouses needed to manage expansion are expensive to create and maintain, so they must utilize the facilities to their full capacity. However, operating at or near full capacity is a balancing act, and breaching storage or handling capacity can be very costly. Replenishment systems need to be both space and capacity-aware to balance the overall workload in the distribution center. Distributors need automated, rules-based solutions to process demand data across multiple customer types and product criteria to maximize forecast accuracy, pick efficiency, and execute diverse orders from a central location.

Section 4: Suppliers can be more critical to inventory decisions than retailers

Supplier agreements and collaboration impact inventory levels

In all verticals, distributors and wholesalers seek to balance suppliers and their retail customers. However, for most retail distributors, inventory decisions are typically based on demand data from retailers. For pharmaceuticals, in some countries, supplier agreements have a more significant impact on distributors’ inventory management than retailer demand.

In some regions, distributors compete for the right to be the only one in the area permitted to sell that drug to all customers. While the supplier benefits from not having to work with multiple distributors when dealing with drugs, the distributor has the burden of getting that product into every channel that needs it. If the distributor owns pharmacies, they will serve theirs, all competing pharmacies, and any healthcare or government needs, typically from the same warehouse.

Further, depending on their agreements with suppliers, distributors may not always carry the costs for the products in their DCs. Sometimes, the supplier may retain the cost until the distributor sends it out, or there may be another agreement for shared investment. However, no matter who carries the cost of the product, the distributor must find space for it and manage any storage requirements, such as temperature, which in and of itself brings a cost to the DC.

All these factors, combined with regional legislation, make it difficult for distributors to evaluate which products they will have at any given time and the stock levels they need to keep. Distributors need a system that enables high operational efficiency and forecast sharing with suppliers. Effective supplier collaboration offers valuable insights as they work together to determine availability targets for their various product types, driving accuracy and minimizing costly over or under-orders. Further, collaborative planning enables distributors to proactively adjust to supplier challenges whenever they see a potential bottleneck.

Section 5: Market shifts, substitutions, and price shifts drive rapid cannibalization

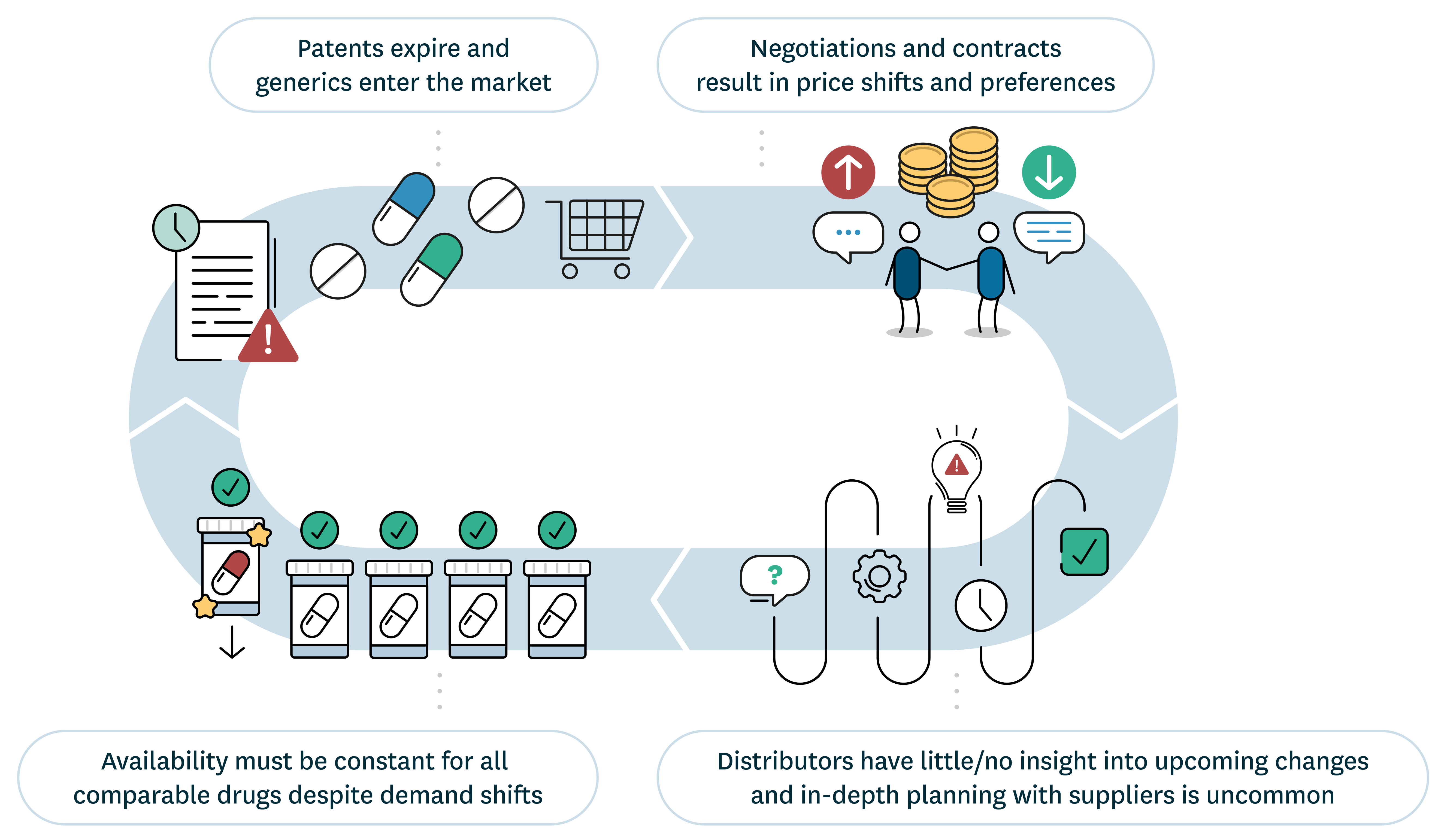

Pharmaceutical markets are highly competitive and in constant flux, and managing a continuous cycle of substitutions is among the most complex issues that pharmaceutical distributors must face. The most common cause of these market shifts is expiring patents or regulation changes that cause an influx of substitute products. These new products drive price shifts, resulting in negotiations between health care insurance providers and suppliers of preferred drugs. In most cases, distributors have little knowledge of how many generic products to expect, when, or who will supply them.

Practices and regulations in some regions can be particularly complex. In Denmark, for example, suppliers bid new sales prices for every product every two weeks. This practice includes prescription and over-the-counter medicines, which means that semi-monthly demand shifts are standard. The result is that distributors may face a situation where a slow or non-moving product is suddenly preferred and cannibalizes the rest. Then, two weeks later, everything could change again.

For prescription drugs, pharmacies in many markets are obliged to suggest the least expensive generic option. Prescribing doctors or consumers may elect to refuse the preferred drug in favor of a particular brand, meaning that distributors must ensure availability for all choices of comparable drugs. For over-the-counter medicines, even though some consumers may be brand-loyal, whatever product is least expensive at the time will cannibalize the others. Distributors must respond quickly to demand across all drug types and factors, such as seasonality, to make the most economical inventory decisions possible.

In all cases, distributors have little to no insight or involvement in the processes that cause sudden market shifts; they can only react. Even if they have a warning that something is about to happen, they have far from perfect data. It is not typical for them to undergo sophisticated planning for such occurrences with suppliers. When managing hundreds of thousands of SKUs, tens of thousands of order lines, and thousands of deliveries per day, distributors need the agility and flexibility of an automated replenishment system to react quickly to recurring and frequent market changes. They also need the capability to forecast based on multiple criteria beyond the SKU level to manage substitutions, regardless of whether they happen due to governmental regulation, price, seasonality, or marketing.

Maintaining balance amid rapid change

It is not easy being the center of a hub, managing products from multiple directions in multiple channels, and keeping everything moving seamlessly. But for pharmaceutical distributors, that is their day-to-day challenge. They must balance suppliers and retailers to meet regulations and availability requirements, manage supply for retail and non-retail channels, and respond to a rapidly changing product market with minimal warning.

Beyond the needs of their customers, distributors are exploring new ways of structuring their businesses and offerings. To remain competitive, they seek to add value to their partners. Expanding assortments bring valuable opportunities but also drive complexity and push capacity requirements to new levels. Emerging customer types and managing both owned and third-party pharmacies, including the trend toward VMI offerings, gives distributors a diverse array of options for operations. Still, they must carefully consider the pros and cons of shifting their current model.

No matter what course they choose, pharmaceutical distributors have a universal truth. Automating replenishment processes with modern technology enables them to process massive amounts of data with the speed required to keep up with their suppliers’ and retailer needs. They can reduce time-consuming manual order management, quickly classify products based on sales patterns and attributes such as active ingredients or price, and optimize safety stocks and replenishment rules accordingly. The resulting forecasting and replenishment accuracy increases turnover rates by serving the same demand with lower inventory levels.