Supply chain integration – Case food service forecasting

Dec 18, 2013 • 9 min

Sometimes it’s simply hard to separate the conversation from the chatter. There are few subjects in the business sphere about which there is so much chatter as the supply chain integration. However, to borrow an idea from the statistician Nate Silver, it’s often difficult to cut through the noise to the signal.

Supply chain integration has been talked about for so long, and has had so much promised on its behalf that, frankly, it’s easy to tune out. Yet it remains a critically important field that seems very likely to yield significant results. Indeed thought leaders in the field are already showing the way.

You can’t live in Finland and be unaware of the challenges facing the communications-and-IT corporation Nokia. Yet for a long time Nokia was a torch bearer for 21st Century industry and at the heart of Nokia’s success was its excellent supply chain management: the right thing, at the right place, at the right time at the right price. This wasn’t simply luck or skill but the result of a conscious strategic investment in the company’s supply chain: process development in tandem with suppliers and the use of advanced IT solutions. Nokia’s strong command of its supply chain has been a big advantage when it has needed to push through changes.

Some of the most successful examples come from players whose power in the supply chain gives them the freedom to experiment and innovate. The global retail giant Walmart has forged a reputation for supply chain innovation. Its clout, both financially and within its own ecosystem of suppliers, has allowed it to invest significantly and make use of a wide range of technology and business models in many different stages of the supply chain. Walmart’s groundbreaking work has encompassed areas such as forecasting collaborative planning, forecasting and replenishment (CPFR), vendor managed inventory (VMI) and radio frequency identification (RFID).

The cases of Nokia and Walmart raise a host of questions for other businesses – whether running their own, smaller, retail supply chains or as suppliers to large retailers. Can other parties in the supply chain benefit from these practices – which often seem to be requirements – as part of an enterprise network? The answer depends partly on how one thinks about supply chain integration, what goals you set for it and your approach to innovation in both processes and technology in pursuit of improving your company’s operations.

Overall, supply chain integration is about knitting together operations of two or more companies. At one extreme two or more firms could substantially function as a single unit, their operations controlled via an integrated IT system. Of course many executives have strong reservations about the degree of interdependence this entails: supply chain partners are essentially locked together for the short and medium term. An integrated supply chain, however, does not have to be so restrictive.

Three Perspectives on Supply Chain Integration

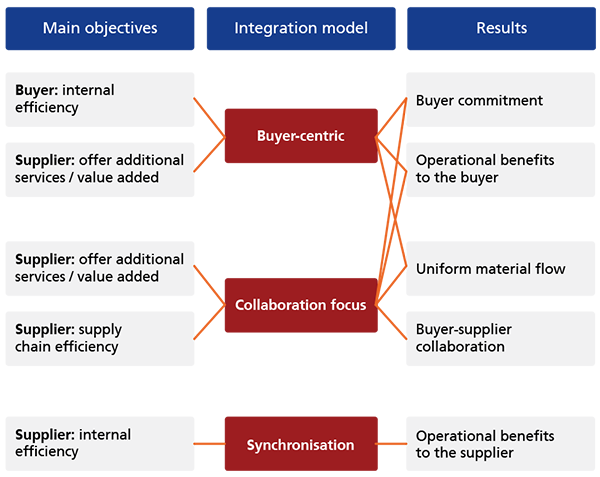

It is possible to distinguish three main approaches to integrating supply chains that differ from one another in terms of the objectives they have and the results they produce: Buyer-centric, collaboration centric and synchronization (see figure 1). It is important to identify the results you desire before investing in process and information system development.

1. Buyer-Centric Integration

A buyer-centric model is all about the efficiency gains for the buyer. The buyer seeks to streamline its operations, for example by reducing the amount of manual work in order processing. The buyer pays for this through accepting greater dependence on the supplier. For its part the supplier looks for a return on its investment through greater customer loyalty and-satisfaction. In situations where the buyer requires their supplier to integrate both supply chains more comprehensively, the supplier may have no option other than to meet the customer’s requirements – and try to leverage the investments when serving other customers.

Another motive for the buyer-centric integration model might be that the supplier is keen and able to innovate in order to offer a better service to its customers. For instance the supplier may provide inventory replenishment services and thus reduce the buyer’s need to devote resources to its re-ordering process. Regardless of the starting point the buyer-centric integration is likely to result in a more even flow of goods as both buyer’s and supplier’s activities are better coordinated.

2. Collaboration-Centric Integration

In a collaboration-centric model the benefits come from the increased cooperation between supplier and buyer. Both parties have a common interest in developing their business and making their supply chain more efficient, more predictable and easier to control. In collaboration-centric integration a channel is created through which the parties can discuss a wide range of issues and discuss them at various levels between their respective organisations. This sort of approach can not only produce much sought after operational improvements, but also a range of unexpected benefits that arise from the supplier and buyer better understanding each other’s businesses.

Typically the relationship between supplier and buyer deepens in a collaboration-centric approach as a result of the time and resources invested in the collaborative relationship. The difference between the collaboration-centric and buyer-centric integration is that with the former the direct operational business goals are secondary, contrary to the buyer-centric approach. In the latter situation, the supplier has a clear motive, namely to stand out from its competitors, either by responding to the buyer’s needs or by providing a differentiated service.

3. Synchronisation

The final model of supply chain integration, synchronisation, is about the supplier making use of the increased transparency to improve its own operations

A manufacturer might, for instance, use POS (point-of-sale) data from the client’s store register system to adapt its own production more effectively when new products are introduced (see previous RELEX publication “Using POS data in your supply chain to react faster to changes in demand”). In this case the buyer might, for example, look to outsource responsibility for replenishment to its supplier in the hope of receiving better service. The supplier in turn can cover the cost of the extra work by reducing its inventory levels as a result of the improved visibility and thus reduced uncertainty.

In fact, a smart supplier always tries to make best use of the integrated supply chain internally wherever possible, even though the original impetus came from the buyer acting in its own interests. In practice, however, reaping benefits from synchronisation might be easier said than done. For example, long production lead times could effectively limit the value added by greater visibility.

Case study: Centralised Food Service Forecasting

An interesting example of a broad supply-chain integration involving multiple companies is the Foodservice Forecaster, a system created for the Finnish foodservice sector. Foodservices cater for almost the entire population in one respect or another – at kindergartens, schools, hospitals, care homes, military bases and workplace cafeterias. Keeping only small inventories they rely heavily on their suppliers; wholesalers and food manufacturers.

Foodservice Forecaster is an effort to help caterers and suppliers work more effectively with one another – suppliers see demand peaks well in advance, while caterers have greater peace of mind knowing that they’ll be able to get the supplies they need.

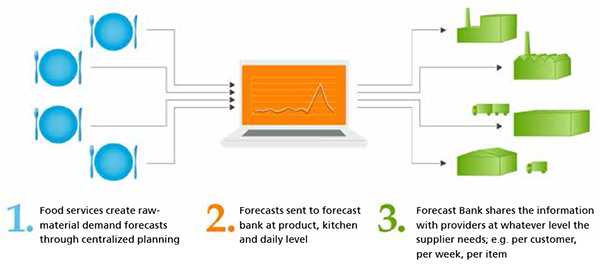

The system requires that caterers plan ahead. Foodservices maintain menus with an estimated number of servings that are then converted into raw material requirements at product level. The forecasts are transferred to the system on product, catering production site, and day level (see Figure 2). The forecasts, i.e. the foodservice sector’s production plans, can then be monitored by suppliers who keep an eye on the required demand levels at, for example, customer, product or an overall week-by-week level. The centralized system also offers the option to suppliers to integrate the plans directly with their own backend systems.

So why is it so useful for foodservice companies and their suppliers to share forecasts?

It’s quite simple really. If a town has, say, 100 restaurants each offering a varied menu and 40,000 diners choose from across those varied menus in the course of a week, demand for particular ingredients is likely to even out across the 100 outlets.

Now think what happens if one company has the contract to cater for all secondary schools not just in that town but across the region. If the company’s planner decides to serve lasagne on Tuesday 5th that suddenly produces a large peak as enough beef to feed 40,000 children on the same day is needed. The demand peak is not predictable for so long as it exists only in the mind of the planner. The problem is exacerbated as foodservices increasingly centralize their menu planning so all their production sites are working from the same repertoire of recipes.

When day care centres, schools and nursing homes in a big city all serve lasagne on the same day, the demand peak for ingredients can even register at a national level. Add to that the fact that specialized foodservice products often have low base volumes, and it’s easy to see the potential for major problems and extra costs for manufacturers, suppliers and caterers alike.

Sudden, sharp demand peaks have serious consequences for staffing, production planning, food waste and delivery, all of which can be severely disrupted. For foodservice companies it means being prepared to make last minute changes to their menus when a manufacturer is unable to meet their needs.

The key point is that this sort of demand cannot be forecast with any great degree of accuracy because no statistical pattern of demand exists. Demand is based almost purely on decisions taken by a very small number of people about which dishes will be served, where they will be served, and when they will be served – to a very large number of people. In other words the demand signal is dependent, not independent.

But though this sort of demand cannot be forecast it can be predicted, and it can be predicted through simple information sharing. The caterers’ raw material requirements can be deduced directly from their menu plans and accompanying recipes. Foodservice companies and their suppliers have a mutual interest in helping one another.

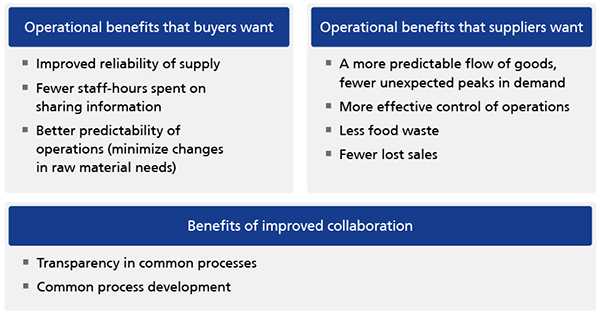

The purpose of the centralized system is to coordinate caterers’ supply chains. This has led to process changes on all sides with the result that of all parties have deepened their collaboration (see figure 3). One of the key objectives is to disseminate high quality forecast information to help providers manage their operations efficiently through the synchronization of the entire supply chain.

The Foodservice Forecaster acts as an industry-specific resource serving its various participants. The goal is to make tangible improvements to shared supply chains and thereby help all the businesses involved. One important finding that’s come from the experience of using the system has been that effective IT solutions – which make the preparation, dissemination, and examination of forecasts easy – are a good basis from which to begin more general discussions on joint development of businesses. When visibility is improved, potential problem areas can be identified more efficiently in collaboration with other participants. For instance some foodservices companies have managed to improve their own operations by identifying problems in their menu planning whenever the projections that have been entered in the centralized system have not been consistent with the actual purchases. On the other side of the equation suppliers are better able to predict peaks in demand. Even ensuring a single correct delivery of several thousand kilograms of potatoes or chicken has a commercial impact, whether the result is less food waste, fewer lost sales or fewer sales at a markdown.

Summary

The message from the Finnish Foodservice Forecaster is clear: when you know what you want and when right systems and processes are in place, then harmonizing and integrating the buyers’ and suppliers’ operations delivers real, measurable benefits. This sort of supply chain integration provides real savings of time and money and cuts waste, which is a great deal more than all the airy talk of ‘working better together’ ever produces.

How to Proceed?

We at RELEX have extensive experience in technology solutions that support supply chain integration – supporting both internal operational control and information exchange between firms. Foodservice forecasting is one example of a system already in use in a networked corporate environment, and where the level of investment of the participants has been very small. The solution acts as a central information exchange joining together several background systems.

If supply chain integration interests you, feel free to contact: jouni.kauremaa@relexsolutions.com. A one hour session is enough to identify the situation in your company and to define development priorities and the first steps!

Sources

Kauremaa, J., Holmström J., Småros, J., ”Patterns of vendor-managed inventory: findings from a multiple-case study”, International Journal of Operations and Production Management, Vol. 29, No. 11, pp. 1109-1139.