Supply chain transformation – Case Motoral

Mar 13, 2013 • 10 min

The American thinker, scientist and patriot Benjamin Franklin famously said: “in this world nothing can be said to be certain, except death and taxes.” Franklin could have added a third certainty; change. Change comes whether we like it or not. Once we accept that and stop trying to avoid it we can think about the more important issue of how to manage it.

However there has been so much talk about ‘change management’ in recent years that the term has started to switch people off. These days every project plan seems to list ‘managing change’ amongst its goals. Such airy aspirations are all too rarely backed up with practical measures. It may be that ‘change management’ is so broad and so abstract a concept that it is difficult to grasp.

Seeing a transformation through to success is rarely about ivory-tower theorising or delivering glitzy presentations. Rather managing change is a practical process relying heavily on good research, hard work, attention to detail and getting stuck in alongside those at the sharp end; the people most affected by the changes.’

One example of a successful transition is a project by Motoral to restructure its purchasing operations. Initially, it was seen as an IT project because it involved implementing a new purchasing system. Fairly soon, however, people realised that the project would change their methods of working and responsibility so much that, in fact, IT would constitute the smallest challenge. Once Motoral had arrived at this understanding, the company began actively to plan and implement the completion of the transformation.

In this article, we will look at the most critical stages of the transition and use Motoral’s experiences to shed some light on what those stages mean in practice.

Change Management Is Real Work

Even carefully planned change does not come about by itself. People often think that when the goal is right and in many cases even commonly desired, it is enough simply to carry out the pre-agreed tasks towards this goal and no more. After that, they believe, everyone will be happy and the new ways of working, having been cleverly thought out, will roll-out smoothly all by themselves.

In reality, almost all significant change involves resistance to that change. Even when change is deemed rational, its estimated or suspected impact on the work community or on one’s position may be subject to resistance. This is why completing a transformation requires effort.

In the simplest terms, change management is an effort to:

- explain why change is necessary and to win hearts and minds”

- hone the planned change so that the end result offers the best possible outcome for all those involved

- reduce unnecessary worries by making it clear what the change actually entails

- ensure that people are helped through the most difficult stages of change considerately, and show them that there is light at the end of the tunnel

- make sure that the new methods of working remain in effect and evolve even after the actual change project.

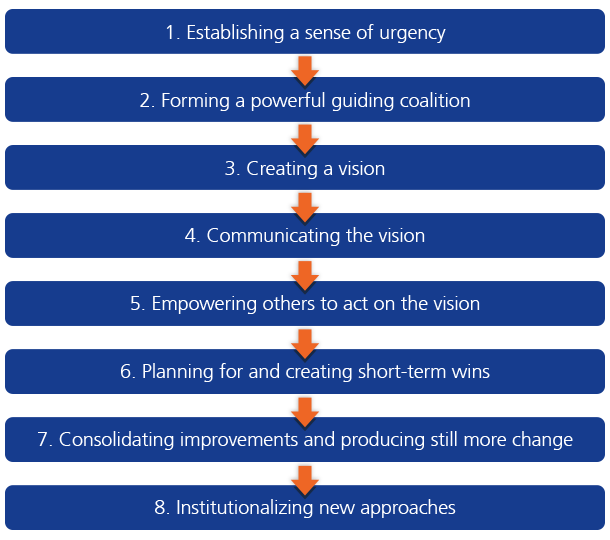

The framework presented by John P. Kotter in 1995 (Fig. 1) is an effective tool for organising the work stages involved in successfully implementing change. Motoral applied the framework to its own project.

An Example of a Successful Transition: Case Motoral

Motoral is a company specialising in spare parts, supplies, tools, and chemicals wholesale. In autumn 2011 the company, together with RELEX, carried out a pre-study that showed how much it could enhance the efficiency of its purchasing operations through better systems support. The pre-study also clarified what kinds of changes needed to be made to existing methods of working and responsibility areas.

At the outset, Motoral’s purchases were the responsibility of around 20 product managers. The company wanted to free those managers to give them time for developing product selection, tasks related to marketing and the customer interface, and monitoring product profitability. Another objective was to consolidate procurement around a team specialising in purchasing, a team that could focus on building its skills and experience and so constantly improve its ability to manage the supply chain.

After the pre-analysis, when Motoral launched the project to restructure purchasing, the company knew that the project would mean not only implementing the new system, but also changing work methods and responsibilities to a significant degree. For this reason, the company began to plan and implement the entire transformation process right from the word go.

1. Establishing a Sense of Urgency

One way to reduce resistance to change is to make the transformation necessary. Necessity dictates that the change has to be made in any case, sooner or later. Getting things moving often requires emphasising urgency. This is needed because, for many of us, our natural response is to avoid any disruption of the here and now by putting off the inevitable.

Motoral helped colleagues understand that change was urgent by comparing their company with leading competitors in the industry that had established consolidated purchasing teams 10 years earlier and adopted systems to enhance forecasting and buying operations. They were helped by the fact that their staff already included employees who had come from other businesses and who regarded Motoral’s operating model as outdated and frustrating.

The necessity was underscored by Motoral’s ever-expanding product range and increasing number of customers and suppliers. With the old model, the amount of manual work would grow continuously and that would require a significant increase in personnel resources. At the same time, control of procurement would decrease, leading to the risk of a weaker level of service to the customers as well as an ever poorer turnover of inventory.

An investment calculation prepared during the pre-analysis was very helpful in setting the transition in motion. The potential, significant financial benefits quickly convinced management to back the project.

2. Forming a Powerful Guiding Coalition

To guide the development, a group of people is needed with enough power to drive the changes through. A small, tight-knit project team is often considered essential for pushing things forward quickly and efficiently. This is often how things work initially, but eventually the transition can slow and even grind to a complete standstill due to a gradual build up of resistance outside the group.

Motoral tackled this problem by establishing a large project team, which was considerably larger in scope than any team they had ever used before. The project team included several product managers with experience in purchasing from the Far East, Europe, and Finland (Motoral’s home market). One member was a new buyer who had been hired on account of the new operating model but who had been familiarised with the old purchasing model so he could help others during the changeover to the new model. The company’s top management was also represented: the managing director, the director of sales and marketing, the director of product management, the logistics director, and the IT director were all part of the team. The aim was to create a large team of experts and to enable them all to have an impact on the end result.

Furthermore, a great number of employees were able to influence the project through various workshops. Not everyone excels during group discussions, so the quieter employees were interviewed separately.

3. Creating a Vision

In order to become excited about change, you have to understand what it entails. Kotter’s insight here is that you must be able to explain the core idea behind a transformation project in less than five minutes, so that the listener understands the subject and becomes enthusiastic about it.

A vision is also important in keeping large projects together. Without a clear vision, a project is easily broken up into several parallel projects that may develop mutually contradictory goals over time.

The pre-study, prepared in collaboration with RELEX, formed the foundation of Motoral’s vision. At the initial stage of the project, the company finalised the vision. It would have been difficult to get the employees inspired about the new method of operation, or even accept it, without a clear and consistent picture of the goals and practical changes.

Motoral included the planned transformation within its strategy, thus ensuring that the new method of operation was in line with the company’s other development objectives.

4. Communicating the Vision

Change causes discomfort and often requires short-term sacrifices, such as the time and effort to learn how to use a new system. Even if employees are unsatisfied with the existing situation, you cannot expect them to be prepared to make such sacrifices unless they believe they will lead to improvements in the longer term. This is why continually communicating the vision behind the change is so important.

Motoral communicated actively and openly with employees about the project. The company held weekly project meetings and published a project newsletter to provide regular information to all employees in the Group. Newsletters told employees what was happening, why the changes were being made, gave a taste of the new system by showing screenshots, and explained each current stage of the project as it progressed.

5. Empowering Others to Act on the Vision

Seeing a transformation through means removing obstacles to the change. When employees have a clear vision in mind, they can start considering their own role in achieving the goals and come up with proposed solutions on their own initiative.

For Motoral, a clear vision and strong support from the owners, senior management, and the project team led to an easy decision-making process.

Changes in the job descriptions of the product managers began during the first stage of the project, before implementation of the new system. Even though they had wanted change for a long time, during the implementation stage of the transformation the product managers began to feel that their toes were being stepped on. Some also wondered whether the planned change would leave them out of a job. At this point having a clear vision stood the project in good stead. The product managers were told in very concrete terms what the purpose of the change was and how their expertise would be utilised in purchasing operations in the future based on forecasts created by the managers themselves. Consolidating buying operations in a separate purchasing team would also give them better capabilities to invest in, for example, design of the product selection, marketing, customer relationships, and follow-up of profitability.

6. Planning for and Creating Short-term Wins

Big changes take a lot of time; if you are unable to achieve and celebrate partial victories, the zeal for development begins to fade away. Kotter emphasises that you do not need to wait for short-term wins to come about in the course of change– they can be actively sought out.

During the implementation stage, Motoral started with domestic suppliers of products in steady demand. Thanks to short delivery times, measurable improvements could be attained more rapidly with local suppliers than those with long delivery times. Furthermore, the risk, at an early stage, of significant blunders that might kill the sense of excitement, could be minimised – it was easy to control the flow of goods from the chosen suppliers, and any errors could be rectified in short order.

7. Consolidating Improvements and Producing Still More Change

When the first improvements have been made, it is easy to kick back and think you have already crossed the finish line – that having identified the target and how to reach it, the rest will simply fall into place. Far from it. Instead, this is the point when you have to kick it up a gear. You have to take advantage of the excitement and trust you have created through the improvements made thus far. Once the foundation for the new operating model has been created, you can carry out new improvements.

As soon as the pre-study was completed, Motoral hired a purchasing manager who assumed total responsibility for developing the purchasing unit, planning the roll-out, and developing all buying operations. Use of the new operating model was expanded carefully by including a few suppliers in the sphere of the new model each month.

At the initial stage, the company invested heavily in improving the quality of basic data used by the purchasing system. After this, they focused on improving the reliability of historical sales data used for preparing sales forecasts and trained the product managers on how to prepare forecasts. Most importantly, Motoral invested in transferring tacit knowledge as the job descriptions changed. The product managers and buyers jointly reviewed what special features were associated with a given supplier, to whom purchase orders should be sent, and what key information staff should have about relationships with particular suppliers and their shipments.

8. Institutionalizing New Approaches

It is important to remember that change is not permanent until it is seen as ‘our way of working’. As long as the old model of operation seems familiar and safe compared with the new one, there is a very real risk that people will revert to the old ways of doing things. For this reason, the new operating model must be rooted firmly in the corporate culture.

For Motoral, this stage is still ongoing. Approximately 80% of all purchase order lines are included in the new system, but product managers still make 20% of purchases on the basis of the old order report. Motoral supports adopting change and making it permanent by regularly reminding staff of the benefits to the company of the new operating model and its effects on the whole range of key indicators. The results to date show a 60% increase in inventory turnover, a 3% improvement in availability, and a 6% decrease in the number of purchase order lines.

From Reflection to Action

As Motoral’s example shows, completing a transformation isn’t rocket science – it is a practical, hands-on process.

Why, then, do people so often fail to carry out change? We believe Kotter hit the nail on the head when he stated that few people have experience in managing several significant change processes. When you do something new, you often learn the hard way.

This is why different frameworks and practical examples are so important. They help us learn from others’ mistakes, avoid some of the unnecessary pitfalls and get up to speed faster on the whole notion of implementing change. Motoral took advantage of Kotter’s framework. Our experience is far from definitive, but hopefully you’ll want to adopt and adapt the best of the ideas that we’ve set out, improve on our ‘pretty good’ approaches, and develop new, powerful strategies of your own! Let us know how you get on.

Reference:

John P. Kotter, ”Why Transformation Efforts Fail”, Harvard Business Review, March–April 1995.”